In a new paper, “Microbial diversity and activity in Southern California salterns and bitterns: analogues for remnant Ocean Worlds”, lead author Benjamin Klempay and a team of investigators from the Oceans Across Space and Time project are seeking to improve our understanding of the limits of life in brines and how that could guide our search for life on other habitable worlds.

Published in Environmental Microbiology in February 2021, Klempay and the team explained how lethal MgCl2 brines could, counterintuitively, be great places to look for signs of life on other planets. Klempay, a graduate student at Scripps Institution of Oceanography working towards his Ph.D. in biological oceanography, studies how microbial communities respond to the intense physiological stresses of living in extremely salty environments.

“Chaotropic stress (the same feature that makes these brines uninhabitable in the first place) preserves DNA, making these brines repositories for genetic fragments from surrounding environments,” Klempay said of the MgCl2 brines. This is one of the key reasons that OAST is so interested in hypersaline envrionments.

Ponds of blue (seawater dominated by NaCl salt), white, pink, yellow, and green (lethal MgCl2-rich brines) are also the subject of Klempay’s research at South Bay Salt Works in southern California. SBSW, like other solar salt harvesting facilities, relies on evaporation to concentrate the salts found naturally in seawater, in order to harvest them.

![Fig 1. An aerial map of South Bay Salt Works. Inlay shows the position of our study site within SBSW, located at the South end of the San Diego Bay, Chula Vista,CA. Satellite imagery from Google Earth. [Color figure can be viewed atwileyonlinelibrary.com]](https://oast.eas.gatech.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Screen-Shot-2021-05-07-at-3.25.52-PM-copy.jpg)

“Being involved with OAST and working locally in the San Diego area gave me the amazing opportunity to advance my research with several field excursions to South Bay Salt Works,” Klempay said. “The chemical conditions in these brines changes dramatically over the course of this evaporation process, mirroring the changes that would have occurred on ancient Mars as the planet transitioned from wet to dry.”

Because the ponds span the chemical gradient from life-filled seawater to lethal MgCl2-saturated brines, Klempay and the OAST team could sample from various ponds at any given time.

“This makes SBSW a very valuable field site and Mars analogue, because it allows us to study the entire process of evapoconcentration and desiccation,” he said. “As evaporation removes water from the brines, the dissolved salts become increasingly concentrated. Table salt (NaCl) is the most abundant salt in seawater, but there are other salt species as well, which have different chemical properties. Eventually, NaCl becomes supersaturated and begins to form crystals, which fall out of the solution (and later get harvested for us to eat!). After NaCl, the next most abundant salt in seawater is MgCl2. It is more soluble than NaCl, and it stays dissolved in the brine even after all the NaCl has precipitated out. The result is highly chaotropic, MgCl2-rich brines.”

Kemplay and the OAST team used filters with tiny microscopic pores to capture all of the microorganisms living in the brines (or dead and preserved) at SBSW. Then, they took the samples back to their lab and extracted DNA from them, which allowed them to determine what was living in each of the ponds.

“We used this to form a picture of how the microbial community evolved over the course of evaporation, and at what point the limit of life was reached,” Kemplay said.

Up until a certain point, life can still exist even as the amount of dissolved salts in the seawater increases through evaporation. This life is characterized by the proliferation of highly specialized halophilic microorganisms. But at a certain point, the brines become lethal and all that’s left are the remnants of what used to live there.

But these hypersaline environments may be the perfect place to search for evidence of past life.

“Within our solar system and perhaps beyond, salty environments are among the most promising targets in the search for extraterrestrial life. Not only are hypersaline brines quite good at preserving remnants of past life, but they are also among the most likely homes for current life in the solar system,” Kemplay said.

In places like Mars, where the planet experienced a shift from being a wet world to a dry one, hypersaline brines would have been the last places for life to find liquid water.

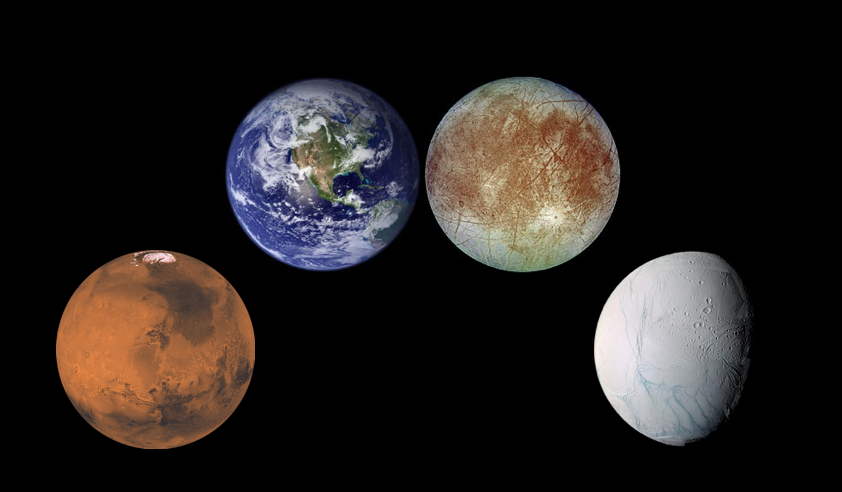

“Liquid water is a fundamental requirement of life on Earth, so a leading strategy in the search of extraterrestrial life is to follow the water,” he said. “As for current ocean worlds, the most promising candidates in our solar system are moons of Jupiter and Saturn, which are too far from the Sun for pure water to stay liquid. But salt lowers the freezing point of water, allowing these moons to have vast briny oceans beneath their icy shells.”

By understanding the limits of life in hypersaline brines on Earth, and how evidence of past life can be preserved in these environments, we may be one step closer in our search for life (or the remnants of it) on other worlds.

The paper Klempay was lead author on made a splash in the world of hypersaline brines, but the work he and the OAST team are doing is ongoing at SBSW.

“We went back to SBSW in 2020 to conduct new experiments and to repeat some of the same experiments with new and improved methods. We’re now able to determine much more effectively which cells are actually alive and reproducing versus which ones are dead/inert. I am also zooming in on the proliferation of halophilic microbes in order to understand how these incredible organisms are able to evolve and adapt so quickly to the rapidly changing conditions in evaporative brines,” Kemplay said.